Does belonging trump ethics?

Think about the last time you were about to join a new group of people. It might have been starting a new school or university, joining a sports team, volunteering for a new organisation or the big one: starting a new job. What questions went through your mind the night before your first day? Was it 'what time should I show up in the morning?', 'how late should I stay at the end of the day?', 'how will I know who are the right people to hang out with?', and that most vexed of all first day questions: 'what should I wear?'.

A brief digression on the ‘what to wear’ question – stick with me … this question is a veritable minefield because you know that every aspect of every choice will be scrutinised and evaluated. Whilst that applies to men too, for women it extends to a disconcerting array of choices: how much make-up is too much/too little, should nails be manicured and if so is bright or clear polish ok, how high should the heels be or are flat shoes acceptable, how feminine is too feminine, should hair be up, down, coloured, straightened or curled, should jewellery be big and bold or small and modest, are drop earrings ok or too flashy, should the handbag match the shoes or is that trying too hard, is fake tan stupid or required, how much perfume is too much and on and on – it's moments like this I truly envy men like television presenter Karl Stefanovic who famously wore the exact same suit on air every day for a year to highlight the differences between men and women's daily clothing dilemmas. If a woman did that there'd be some kind of cosmic meltdown. In Karl's case, nobody even noticed. But, as indicated, I digress.

The point is, before we join a new group of people most of us wonder what the current members of that group will find acceptable and we want to do whatever that is, or at least understand the implications if we decide to do things differently. Why is that important to us? Why do we think about it before we join the group? Because we want to fit in. To be accepted. To belong. The need for belonging is one of the strongest needs of every human being. It drives an enormous amount of our behaviour.

The wonderful social researcher Brene Brown said: “A deep sense of love and belonging is an irreducible need of all people. We are biologically, cognitively, physically, and spiritually wired to love, to be loved, and to belong. When those needs are not met, we don't function as we were meant to. We break. We fall apart. We numb. We ache. We hurt others. We get sick.”

Belonging is so strong a human need that it will almost always trump an individual's own sense of what is ethically right and wrong. Take the recent experience of Wells Fargo as an example and cautionary tale. James Heskett's column in Harvard Business School's 'Working Knowledge' online journal describes the way thousands of the bank's employees behaved unethically: “ … the goals on which the incentives were based were so daunting that they raised the temptation to cheat by establishing fake new accounts and even transferring token amounts of funds between these accounts without customers’ knowledge. When the practice became so prevalent – 2.1 million accounts from 2011 to 2015 – it began to generate numerous customer complaints and evidence surfaced regarding a systematic cover-up of the practice in the ranks. Wells Fargo announced in September 2016 that some 5,300 employees were fired. The action was taken by leaders who claimed they were unaware of the practice; nevertheless, the board replaced CEO John Stumpf and clawed back some of his compensation. The monetary and non-monetary costs to the financial institution in penalties, fines, and loss of trust began to mount.”

It seems obvious in this case that the way the incentives were designed was encouraging this behaviour, but the main question it begs for me is this: why did so many people, literally thousands of them, do something they must have known was unethical? I would argue that it was about belonging. Hitting targets was considered successful behaviour in that group and even if hitting those targets involved unethical behaviour, thousands of people decided that belonging was more important than their own ethics. Now granted, 'belonging' in this example involved receiving a pay cheque and lack of belonging would have involved losing said cheque, but this only reinforces how important belonging is, it's particularly high stakes for paid members of organisations.

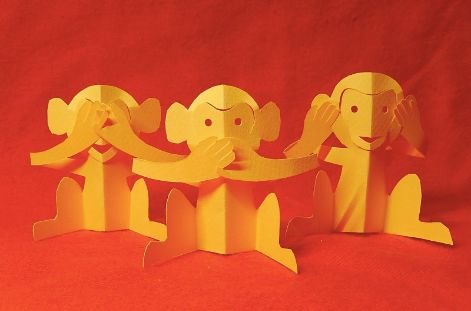

Many of you will have heard the story about monkeys and bananas that is used to describe organisational culture.

It goes like this: a group of monkeys are put in a cage and a bunch of bananas is suspended out of reach above them. A stepladder is added. As soon as one of the monkeys climbs up to grab a banana, that monkey is shot with a water cannon. This negative reinforcement is repeated until all the monkeys stop trying to get the bananas. Then one of the monkeys is replaced by a new monkey who has never been shot with the water cannon. New monkey immediately climbs the ladder but is attacked by old monkeys who know that bad things happen when you climb the ladder. So new monkey learns not to climb the ladder. Then the old monkeys are systematically replaced with new ones until the whole group is made up of monkeys who have never been shot by the water cannon but, and here's the kicker, none of them attempt to climb the ladder. Why? Because they've all learned that bad things happen when you climb the ladder.

In other words, the new monkeys quickly learned what was successful behaviour in the group they joined - and complied with that behaviour even though they didn't know where it had originally come from or why it made sense. It had simply become 'the way we do things around here'.

The origins of this story come from an experiment conducted in 1966 by Gordon R. Stephenson from the Department of Zoology in the University of Wisconsin called 'Cultural Acquisition of a Specific Learned Response in Rhesus Monkeys'. As you might suspect from the title, the original experiment is a little less exciting than the story that grew from it, but if you're interested you can check out the research paper here.

So what conclusion can we reach from all this?

Humans will adopt the behaviour that is successful in the group they join.

The monkeys quickly adopted the behaviour that worked in their new group. You are likely to wear what is considered acceptable at your new job. You might even behave unethically if belonging to your new group depends on it, particularly if not doing so would involve losing your pay cheque. Turns out we actually are, in the words of the absurdly talented Tim Minchin, just ‘monkeys in shoes’.

Why does this matter?

If humans will adopt the behaviour that is successful in the group they join – even if it's contrary to their own ethics – that means you can't rely solely on the individual ethical standards of your people, no matter how exemplary they may be, to ensure the ethical behaviour of your organisation. And selecting only highly ethical people to join your organisation, or indeed only people with any other attribute, won't guarantee anything either.

You had better figure out what behaviour is considered successful in your organisation. Whatever it is, that's the culture of your organisation and it's happening whether you're actively managing it or not. If it's behaviour that's unethical or in any other way unhelpful to successfully executing your strategy, you need to know about it so you can change it.

Wells Fargo didn't have 5,300 rotten apples in its barrel. It had a rotten barrel. That's essentially what culture is. It's the barrel. That's why Peter Drucker's famous quote “culture eats strategy for breakfast” is right on the money - yep, I'm aware of the debate surrounding whether or not it was Drucker who said it, but somebody did and he or she was right.

No matter what it says on your 'strategy on a page', that will pale into insignificance in the face of the human need for belonging.